When Something is at Stake – a Conversation with Truls Lie on Film and Reality

By Nina Toft

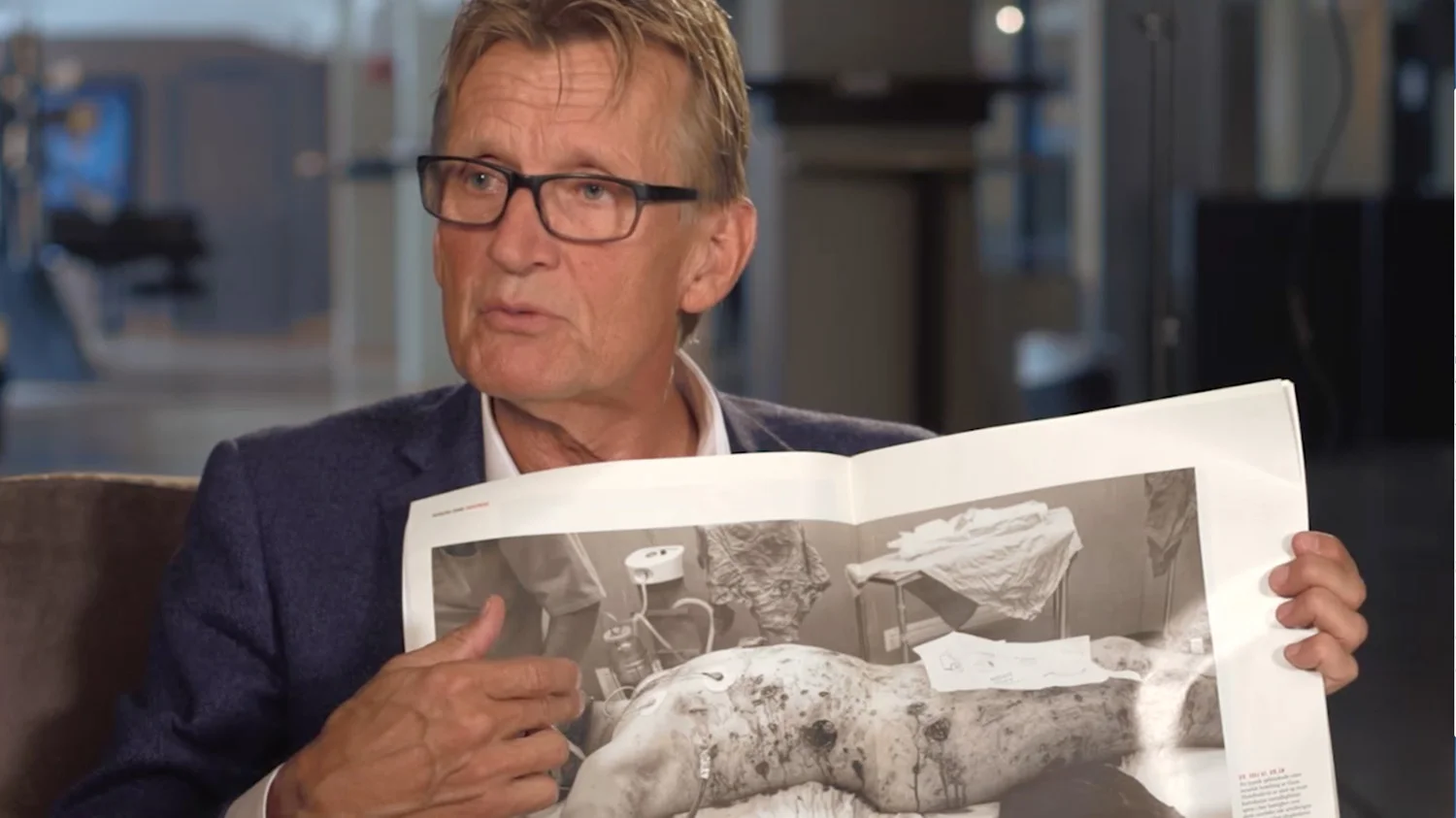

Truls Lie is a filmmaker, editor, journalist and critic educated within philosophy. He was the editor of Morgenbladet (1993-2003) and was the editor and publisher of the Norwegian edition of Le Monde Diplomatique for a ten-year period. His work as an independent filmmaker includes such films as Det forførte menneske – Jørgen Leth, Haiti and Mads Gilbert on Gaza.

You attended the screening of the video art programme ”An Investigative Perspective” curated by Hilde Honerud and myself for the Norwegian Short Film Festival in Grimstad this year. During the debate after the screening you had a few comments and questions which you elaborated on further in a commentary piece in Le Monde Diplomatique, paying particular attention to Margardia Paiva’s film “I Will Hurt You Before You Hurt Me”. In relation to the film, which mixes staged scenes and illustrative images with real-life accounts, you asked to what degree aesthetically minded visual artists are ethically responsible for their films. You ask how honest a director should be in the “contract” with the audience. What rules would you say are applicable to the documentary genre? And can you elaborate on what you mean by the director’s contract with the audience?

As a visual artist working aesthetically, you may believe that your practice is exempt from reproducing the world truthfully because the role of a visual artist allows a certain freedom of expression. However, artists can’t just relive themselves of this responsibility, but have to have an ethical relationship to the world. When you make a film, which is about reality, like Margarida Paiva has done, where you are led to believe that you’re hearing the voices of women that have committed murders, you become emotionally invested. You become convinced that these people really mean what they’re saying, but it turns out that they’re just actors. The reason I work with documentary is that I find that events seem stronger when they come from real life. How much of life should we invest in fictions? I’m a little bored of fictions.

When I make films I often travel to parts of the Middle East, like Israel and Palestine; places where there are a lot of things at stake. It’s my opinion that it’s my task as a filmmaker to have an ethical and compassionate interest in other people. This isn’t so much about me or my signature, but about conveying the situation of the people living in these conflict-zones. I made a short film from Gaza about Mads Gilbert a few weeks ago. Have you seen it?

Yes, there were many strong images.

I use strong images. In the film that follows Gilbert I show small, dead children laying in rows in the hospital in Gaza, and the men sitting behind them, almost like an audience. These images have some strong connotations and are hard to look at for some people, but the film has been watched over 25 000 times so far.

You’ve chosen to distribute the film online?

Yes, I uploaded it to both YouTube and Vimeo. It’s the first time I’ve distributed a film this way. It’s a new medium, and I feel it’s a little like going back to the 1970s attitude of “doing it yourself”, where it’s all about being involved in every step of the process around the film. 25 000 people is after all a sizeable audience, equivalent of the film being screened at roughly a hundred festivals.

I made the film on a shoestring budget and in my spare time, but I received comments from all around the world. A woman wrote that she ended up staring into the wall with her 15 year-old son after watching it; the film gave her such a strong experience that she couldn’t find the words to express how she felt. The context Mads Gilbert gives the images justifies their use, and without him to contextualize they give no meaning. In the worst case it would have become a snuff film – where the intention in itself is to show the killings. Mockumentary is a genre that stages reality. I saw the film Russia 88 (2009) without being informed beforehand. Handheld camera use all the way and lots of intimate shots. I thought it was real, but suddenly the one character kills the other. I was shocked by the sudden violence and was tricked into getting emotionally involved under completely false pretences. It felt like a form of abuse.

Truls Lie, Mads Gilbert on Gaza (2014)

Truls Lie, Mads Gilbert on Gaza (2014)

Truls Lie, Mads Gilbert on Gaza (2014)

When I watch film nothing excites me more than when filmmakers surprise and challenge me, when something isn’t quite what it appears, when the film takes an unexpected turn. When I’m challenged to think and I’m maybe even forced to change my opinion, I feel something. The film has succeeded in making me think about the content, both the theme and how it is represented. In Paiva’s film it was the ambivalence and friction between her representation of reality and fiction that kept me captivated throughout the entire film. For me it was the distance created by the illustration-shots that enabled me to empathize with the women and their choices. In a certain way I identified with them, placed myself in their situation, because while the story is about a specific woman, her experiences, trauma and actions, it is also a story that could be about any woman at all.

I liked the film a lot – I’m not dismissing it as bad. Even considering that it’s fiction it’s a film with exciting content. When women kill their own children there is something psychological at play that engages me, but I still find the form troubling. To a certain degree it’s also about what ends up being staged; if the women had discussed clothing choices I probably wouldn’t have cared if the voices were real or not.

Don’t you feel manipulated when the structure of a film is speculative? Dramaturgy, climax, catharsis and deliverance - all these elements that are supposed to provoke an emotional reaction while viewing a film. Take The Act of Killing for example. It’s a film with an intense theme, where they create a film within the film, but there isn’t any dramaturgical structure or catharsis; you don’t get the feeling that any of these characters are capable or willing to change their life around.

Margarida Paiva, I Will Hurt You Before You Hurt Me (2013)

Margarida Paiva, I Will Hurt You Before You Hurt Me (2013)

I understood the Act of Killing as a form of therapeutic exercise for them, were they reach some realisations about their actions through participating in the film.

I don’t think the film had such a clear narrative development, but it’s an incredibly strong film thematically. There is a lot at stake and it touches on quite a few ethical grey areas.

Yes, the Act of Killing provokes and engages. I have an ambivalent relationship to the film, even though I find it interesting and useful. It employs a risky set of methods, but in terms of ethics the film leaves me with an uneasy feeling. The characters are used in a game that they can’t fully understand the ramifications of. They want to participate, but don’t understand what they’re participating in.

No, they don’t. But most documentarians exploit their subjects; they exploit them and leave them in the same state they found them in. A documentary can cost several million to produce, sums that in theory could have been spent on giving the subjects a worthy life instead of making a film. In that sense there is a lot of cynicism around. Emmanuel Levinas is an important philosopher in the discourse around The Other and questions tied to what it means to have a meaningful existence. He asks about what can be considered important and unimportant, rather than right and wrong. How does something become important in a given situation? As a society we create doxa for what it means to be a person. Why does it for example give meaning to be an editor for a web-based journal in 2014, why does this constitute a portion of meaning in your life? The norms that constitute opinions change with the times: religion, nature, art and philosophy are all categorizes that create doxa that are perceived as truths in their time. What constitutes meaning today? Perhaps visibility in the media, being seen, being read and as a consequence being acknowledged.

I would think that for documentary filmmakers and journalists relaying something of personal importance gives meaning.

For a few this is the case, but the rest do it for the attention, it’s inherent in doxa. I’ve been interested in the notion of reality for a long time, and after 20 years as an editor and publisher in both Morgenbladet and Le Monde Diplomatique I’ve become increasingly interested in content. I’m from another field than the film business and I wish there where more intelligent films made – films that think. The essay film is in my opinion a genre of film that thinks, with Chris Marker and his production as the most central and important example. The essay film finds itself somewhere between fiction, video art and documentary, it’s idea-based and it follows a theme instead of a main character. It typically isn’t character driven, but is driven forward by a thoughtful voice, a voiceover that speaks directly to the viewer. The essay film has a personal, subjective, dissociative, experimental and explorative form. It’s part of the definition of essay to experiment and test – often the task of the heretic. The essay film is heretical and rebellious; it attacks a theme and fights for something. It’s a tradition that encompasses filmmakers such as Harun Farocki and Jean-Luc Godard. Farocki is an excellent example of a filmmaker that dares explore and play with how film is made.

I’ve become acquainted with Farocki’s production through exhibitions in galleries and museums. A large number of his films were shown at The Museum of Contemporary Art here in Oslo a few years ago. Does he also show his work in the cinema?

Yes, I saw a retrospective programme of his during Lisbon Docs where there was an emphasis on his work being shown in both types of venue.

A visual artist working with moving images probably feels freer in regard to method and genres, as work by visual artists often seek to challenge established conventions. The cinema is a different arena from the gallery space, with the theatre in my opinion having a clearer structure, as films are shown from beginning to end for an audience which sits concentrated during the film –the contract of the cinema. In the gallery space the viewer is freer and can move about the room, re-composing the individual parts as they move around, stopping to contemplate or to read supplemental materials. The viewer decides the time spent in the exhibition. Moving images are presented within the framework of the exhibition, the room and in relation to other works, but are rarely categorized as documentary, essay film and so on.

When visual artists that work with film wish to show their films in the cinema, they normally don’t categorize easily within the genres of the film world. They don’t necessarily live up to expectations of the cinema audience. In my opinion this is a major communication problem. What is your opinion of this?

If you have a challenging, high quality film, which requires a certain degree of contemplation, the cinema is often the superior space. In a gallery it’s just too easy to move along. A gallery can be a little like a TV and a remote control, it’s easy to zapp. It’s easy to move away from a monitor, also because it can be hard to concentrate in a white cube with lots of other distractions.

I’m very open to experimental work by visual artists. The shorter format works fantastically for this. It’s about time that filmmakers realize that only about every fifth documentary actually needs to be 90 minutes long. This is an area where I hope that documentary filmmakers can find inspiration from films by visual artists.

Isn’t it also a question of distribution, a film needs to be a certain length to qualify for cinema release?

Yes, within the festival circuit there are a few structures that affect the documentary genre. I often enjoy films by visual artists; they engage me because of the aesthetic focus. Documentary filmmakers often lack the schooling to appreciate that visual images are a fundamental aspect of how they communicate. They’re too concerned with a journalistic approach or with building an emotional response to the main character. I greatly appreciated An Investigative Perspective and that’s why I mentioned that art academies very well could be the new film schools. Visual artist are more experimental and are in that sense often closer to the essay film in form. I think audiences today expect to be surprised, they want to see something new.

When I’ve shown video art in the cinema my experience is that the audience finds it challenging, and I’ve also received some negative reactions. In my mind the biggest challenge to the audience is that nothing is defined beforehand, the films in a programme can require quite different modes of viewing, and the audience has to work a lot on their own. Audiences expect to be led - or seduced – and when a film requires engagement from the viewer they quickly become bored and restless.

You talk about being seduced – Baudrillard has written a very good book on seduction, (Ed. Seduction 1992). He says that to let oneself be seduced, se-duction, is to be led away from yourself, while pro-duce means moving forward, going straight ahead and overstating things at times, He considers the first term female and the second male. There is so much more to seduction.

There is commonplace idea of the cinema as a place one goes to be led away from the self – into a fiction.

Another way to be led away is to visit Film fra Sør to watch the documentary The Salt of the Earth (2014), about a photographer that has seen hell on earth. Then you’re truly led away from your own safety. That’s also one way of being led away.

What makes something real in film? We’ve talked about films that exceed the boundaries of documentary and fiction, but I’d argue that all film is constructed. When a camera enters a situation there will always be a degree of staging, because the presence of the camera often changes or affects the chain of events and provokes reactions. A filmmaker that attempts to relay from reality works towards pointing at something, focusing, simplifying and assembling… There is no escaping that film is a manipulation and displacement of reality, no matter how much it emerges from that same reality. An interview such as this is a very artificial situation, while it’s still very real that we are sitting here talking.

During the debate at the Norwegian Short Film Festival in Grimstad my questions on ethical responsibility where rejected by the head of the festival Torunn Nyen with the argument that all film is light drawn on a surface. But film is more than just that. One example of this is Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait, an amazing collaboration between director Ossama Mohammed and the Syrian activist Wiam Simav Bedirxan. It’s a film that contains images of people dying, while a commentary reflects on the current ongoings in Syria. Watching this film is a very real experience to me.

Both photography and film have this strong indexical relationship to reality because they consist of signs and traces from reality, but that does not mean that what we see is necessarily real. This delineation can be difficult to interpret for the viewer. It is real, but it is film. What matters in the end when I watch a film on an actual event, is if the film makes me respond emotionally and if it engages me in its subject. If the real is defined by a camera looking at something that is playing out in that very moment I think that’s too narrow a definition.

You say that if a film engages you, it can be considered a good film. I don’t consider it a formal requirement that there is an emotional reaction form the viewer for the content of a film to be defined as real. Authenticity, as it’s defined in philosophy, is an existential experience of something being near human terms. To experience the essential in human experience. Existentialism, with Sartre and Kierkegaard, was concerned with being until death. To recognize oneself as something temporary, affected by values and the materiality of the world, is to recognize oneself as vulnerable. If you see a film that shocks you out of societies norms and the current doxa it can be an authentic experience, in other words a film that touches on something essential in human experience. Some films are able to do this by being near real situations while simultaneously commenting insightfully. Take for example A Grin Without a Cat, an important film by Chris Marker about the revolutionary movements of the 1960s. In my opinion it’s fundamentally about staying true to ones own integrity.

This seems like a way to stay honest. It’s one thing to stay true to oneself and one’s own intentions, but if you’re about to do something that reaches beyond your own moral limits, or you’re wondering if your heading in that direction, you need to think it through thoroughly.

Chris Marker, La Jetée (1962)

Chris Marker, La Jetée (1962)

Chris Marker, Sans soleil (1983)

Chris Marker, Sans soleil (1983)

Chris Marker, Le Joli Mai (The Merry Month of May), (1962)

I attended a debate on film and visual art arranged by Atelier Nord and the Norwegian Critics Association last year. One subject that showed up during the audience discussions was that filmmakers want more freedom in their production; they want to make films that are less bound by rules and conventions, independent of a producer as an additional and costly part of the process. Several of the participants pointed out that this is impossible within the current framework for production support, screening and distribution. As a filmmaker, do you find that you can make films in the manner that you feel suits your message best? How do you feel the system of production support, distribution and screening inhibits your ability to make the films you want?

It’s often the case that the most exciting filmmakers also are the ones that don’t fit the support system. I can’t say much about the world of fiction, but in the documentary field NFI’s instance on requiring a producer can be destructive for film projects, as many documentary filmmakers do most of the work themselves. Producers are supposed to find financing, but a large part often ends up being spent on wages and administrative expenses. Often there isn’t much left after the producer has taken his part. I think it’s a mistake to let producers take care of documentary filmmaker’s finances. The funds could instead directly to the director, who could choose to hire a producer for certain tasks as needed. I’ve learned to do most things myself, including camerawork, editing and project management as not to be overly reliant on support schemes when making films. There is also a certain anti-intellectual attitude and an exaggerated focus on character driven storytelling in the Norwegian support scheme system. I’ve noticed that the short film consultants and the scheme “Nye Veier” has opened up for more experimental projects, but beyond this the strategy is still to build up an industry and producers, an approach that is problematic for the documentary genre. I think there could be many more intelligent and thoughtful films if more people were given a chance. I’ve argued for years that more people should get development support with a thinner bottleneck for production support. The criterion of films having to reach a large audience is overemphasized. If you want to pull in the masses you only end up with mediocre films. Why should we need to reach as many people as possible all the time? After all, unlike NRK, it is NFI’s task to support artistic use of the moving image.

Now that the usage of images is accelerating extremely fast, we document and publish our lives without necessarily taking the time to reflect over what this practice does to us. Some do, but in general these lines of thinking struggle to keep up with what’s constantly happening here and now.

You could really wonder what it is we’re actually doing? 200 years ago there was no such thing as film. Why do several hundred people bench themselves in a cinema at once to watch a movie? And why do we even produce films at all? We live in a society that that needs more people to learn to interpret images, be critical and discuss what is manipulative and not, rather than just consuming film. Film is much more than just entertainment. In the 70s and 80s Gilles Deleuze argued that in the future we would be able to learn to think with images rather than with concepts. Deleuze believed that thinking in this way allow us to better understand the relations between things. Could this be why we make moving images?

It could be interesting for my own part to go back and look at what originally motivated me to work with the medium. I remember the first time I was given a camera, a small pull-out with a flat roll of film – was it 110 it was called? I remember that it came in an orange box that I kept hidden like a treasure. I brought it out to examine it all the time and it was only after long deliberation that I decided that something was important enough to be photographed. The camera made me think of all sorts of things as a potential image. I spent more time thinking of images than taking them, which I suppose I still do.

Yes, the thinking individual has a philosophical need to understand his or her own actions.

For me photography is about looking and reflecting over what I see.

I’m working on a film called The Significance of Freedom where I talk to women in the Middle East about what freedom means for them. Whether it’s spiritual freedom, freedom in the family or in society as in freedom of speech. I’ve been to Palestine, Cairo and Beruit and I’m going to Teheran next. The important part is how I interpret the meetings. Regardless of if you call it staging or interpretation when you encounter someone and have a long conversation, as we have now, it has to be mediated forward. In that sense reality is nothing more than a raw mass.

Translated from norwegian by Nicholas Norton