THOMAS ØSTBYE

Destroying Our Film

To me, working with documentary means dealing with something that I perceive as outside myself – that I cannot fully grasp. I have my ideas and opinions that direct the work, but in the core of the process there’s also an attempt to get closer to something that’s infinitely complex. My documentary method has been to use the camera and setting to narrow the field of view in order to simplify and control it so that the uncontrolled elements pop out and are highlighted. With 17,000 ISLANDS I’ve taken a somewhat different approach.

17000 ISLANDS was made in collaboration with Indonesian director Edwin. [1] We both thought collaboration would be hell, since it’s impossible to have a shared vision, it’s dull to compromise, and we’re both used to spending a lot of energy trying to control our projects. In the end, 17,000 Islands became an interactive documentary – something neither of us where interested in before this project started.

We had a shared interest in the relation between the world and our representation of it, so we decided to make the problem of collaboration bigger, to invite it and build on it, embrace this threat of losing control. By losing control we hoped to let another part of reality into our film that we wouldn't have been able to see with our usual controlled practice of filmmaking.

We thought this would be interesting to do in a controlled environment, and for this we chose Taman Mini Indonesia Indah (Beautiful Indonesia Miniature Park), a Disneyland-style park in Jakarta built in 1975 by the Suharto regime. It’s a miniature version of Indonesia that presents the diversity of the country in a condensed and manicured form – an idealised image of the conflicting Indonesian reality used as propaganda to present Indonesia as one unified nation under the state motto: Unity In Diversity.

We shot there without planning or discussion, randomly picking a lens before going to a location, or spending the day following a stray dog that guided us through the park. In this way we discovered something unexpected, something alive outside our ideas. But of course, during the editing of the movie we started to simplify our ideas again. Just as Suharto simplified the image of Indonesia in Taman Mini, we could easily simplify the image of Taman Mini.

To me, this was a question of Orientalism: going as a European to an exotic country and making a documentary on the political and cultural situation seemed all to familiar as the standard procedure of documentary filmmaking. Therefore we decided that the work should be influenced by several views, and different people should be able to re-edit our movie. It would be done on the internet so that it would be easily available to a broad range of people. This would possibly bring some diversity back to our picture of Taman Mini. When we show this project at film festivals, I restore the user-made films with the original HD material , and make screenings of these films in a normal theater, like normal shortfilms, regardless of whether we like or dislike the films. When the material from our film has been used in ten short films, it disintegrates, leaving only the least popular clips. Eventually our film is destroyed altogether and replaced by a multitude of short films by different users.

What did letting go of our directors’ cut in favour of this multitude of short films do to the end result? Did it add new perspectives on the images we made, or on the reality that we where shooting? In André Bazin's terms, did we ‘reveal reality, or add to it’? It certainly showed some unexpected links and possible meanings in the video material that we hadn’t recognised before. In some cases, especially with Indonesian users and those who have a relationship to the park, it gave some interesting views of Taman Mini.

I believe that we have an intrinsic tendency to make meaning out of images, and this process easily generates meaning that has lost any connection with the reality that took place when the image was shoot. This process is closer to expressing yourself, or your encounter with the image, than it is to opening up to the world and its complexity. But through it we’re gaining a connection with a very important part of reality that the representation Taman Mini was constructed to hide: many different views from a variety of people. These multiple views and realities might well be more essential to Indonesian reality than Suharto’s attempt to create a unified image of the country.

[1] Like many Chinese Indonesians, Edwin only has one name. His most recent feature film is Postcards from the Zoo (date?).

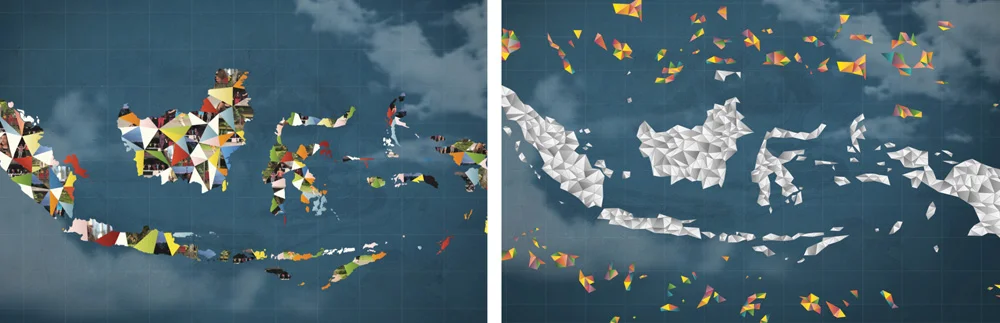

On the website 17000islandsinteractive, our film is presented in small pieces collaged together to form the official map of Indonesia. You can browse and watch each clip, - or you play them in the order of the directors cut. You chose whatever material you would like to use.

You use this material for editing, but in a totally new and non-linear way; by building an island with the material. Theese map images are also a linear films, -based on the image you create.

You might like to edit in a traditional linear way also, adding titles and voiceover, -but beware, your island and film is connected. The island shape will change when you edit, and so will the linear film if you re-collage your island, - island and film are bound together.

Please save your island film, and it will be part of the 17000islands catalogue, and be placed on the map.

We started with our official film and map, and as you make your own island films with our material, they are placed in the map.

The material used by more than 10 users will be deprived from our original directors cut. The official map fades, a new map consisting of user islands is growing on the website, and the directors cut disintegrates, - leaving only the least popular clips.

If you try to watch the directors cut, it will be deprived of all the clips already used up. To find any of these, you will have to visit other people’s island-films and borrow from them.