EIVIND H. NATVIG

A Certain Level of Discomfort (the turning point)

‘Eivind H. Natvig was the epitome of the young up and coming photojournalist’

Was?

When did it end?

Seriously.

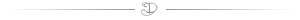

I wake up on an old mattress in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The grey floor is covered with a thin layer of dust. Not the visible kind, but the sort you find in overpopulated cities with heavy traffic. The kind that coats everything. Last night I returned from two weeks of assignment in the Middle East, working 14–18 hour days. Body and mind are drained. I literally collapsed onto the mattress. Slowly waking up late considering the level of noise outside. With absolutely nothing to do this morning, I decide I might as well stay in bed for a while. After keeping up a daily routine of production for longer than I can remember, the decision feels legitimate. I’m in a room with whitewashed walls and nothing interesting to look at. Nowhere to rest the eyes. It’s a space devoid of visual impressions. The pounding sounds of Dhaka, five storeys below, seep through the windows. The room, which closely resembles a cell, is ten square metres of safe haven. Outside is a mega-city in the most densely populated country in the world with an unimaginable amount of traffic and unknown numbers of human beings going about their lives. I just need a bit of rest before confronting it. A slow day to recharge the batteries. Lack of rest.

“At best, these photographs will be forgotten after a day or two. Perhaps a week.”

Soon I realise that this isn’t about a lack of rest; it’s about an abundance of fear. A fear of going out to interact with strangers, stealing their image. The past months have involved a massive overload of intruding into lives. Now it all feels pointless and futile. At best, these photographs will be forgotten after a day or two. Perhaps a week. Hasn’t it all been told and re-told to infinity? Will the stories we can register on a mere superficial level even enlighten or educate the readership on any but a worthless level? The allure of photography is gone. The adventure of going out, engaging with the unknown and unpredictable has disappeared. The need to record situations and freeze moments, all the photographer’s clichés. They’ve become just that;clichés. What truly is the value of documenting contemporary life? The only significance of the work I’ve been doing for a long time is to fund this current lack of productivity. To fund what should be valuable weeks. Time bought to balance out the assignments. A few short weeks of freedom.

I stay in my room. Registering the noise from the world outside.

It’s early December, and a short month from now a staff job is waiting in Norway. Dhaka is my last refuge for free photographic expression, story-telling and adventure for a while, yet I have no energy to utilise it. I read, watch movies and drift in and out of sleep. I think about photography as a profession. The media and visual journalism world I know back home feels for the most part like a group of self-congratulatory egos. The burning desire for story-telling seems lost on my colleagues in the north. Boastful conversations over beer in dimly lit pubs appear more of a motivation than finding and telling stories. I’m deeply disillusioned. I wonder if anyone other than me remembers the screaming father and the dying child. I wonder if it ever truly reached anyone at all, my invasion of that most intimate moment. I was welcomed, but for what? To be their voice? A witness? We feed into the same pool of photography. We head out to create images considered good, solid photography. Again and again. If it leaves no dent, no lasting impression, it’s as if it were never seen. If an image isn’t seen, it doesn’t exist. What about all the images that are forgotten? The images that refused to be viewed.

“A black hole ends up being my saviour and path to light: pinhole-photography. The only goal: to produce one image today.”

Morning turns to night and before long a week has passed. Nothing has changed. I imagine being a prisoner before his impending release. A black hole ends up being my saviour and path to light: pinhole-photography. The only goal: to produce one image today. Little do I know that this is the beginning of a life-changing addiction. The sun advances across the horizon and it’s not until afternoon and large amounts of coffee that pure willpower unlocks the door, after one week on the mattress in the sanctity of my cell.

The streets are kind today. People are kind today. But then again, they always are here in Dhaka. Kind and inspiring. I find my image. I go back out again. Every day. A newfound joy is born out of this photography rooted in journalistic method, but whose visual expression is completely subjective. Purpose is reborn, and even if this isn’t important work, it matters to me.

Peace and solitude in one of the most hectic cities in the world. It feels like a dream out here, floating through the friendly streets. The joyous exploration of familiar places, rediscovered by the magic of photography. Providing a whole new perspective, making the experience more important. It’s only while editing the images at night that I discover a new planet. A planet existing just outside my home. Passion and energy returning day by day. I ask my future employer to postpone that first day of work in order to stay on the road a while longer. I ultimately and unwillingly go home without any idea that these playful days in Dhaka will be the first steps to exploring Norway.

A fortunate turn of events. Something about the baggage from Bangladesh has reignited the passion, but with a newfound liberty. I quickly realise that my new employer is willing and able to try new things. To explore the subjective visual language. Even more importantly, the writer I travel with sees the opportunity to experiment as well, and when we return home the art director elevates the content we’ve come up with.

However, there’s still the constant feeling of being imprisoned. Even if everything is in place for a great job, I’m overtaken by claustrophobia, and resign four weeks after my first day. Why should I register events photographically if I can dream images? When I can use the power of photography to re-invent known objects and situation? Offer new perspectives and help guide people towards new impressions of their surroundings?

What I’ve come across just weeks earlier across the planet has got into my veins. A drug much too powerful for a mere hit a month as a staffer. I need my daily boost. These are the months when You Are Here Now is born from a wide range of stolen explorations of Norway. Whether in the moments before, after or during assignments, the occasional frame is set aside, until one day it arrives at critical mass and evolves into something bigger and deeper than these single frames. It is now an addiction. A random combination of events have led me here. From the refuge in Dhaka to the polar winter in Finnmark in a few weeks. Assignments across the country temporarily cure my itch, but it’s not nearly enough and I need to dig deeper. I decide to make myself homeless and live on the road for a while. I uproot my life and head out. No strings, no ties; just a vast and endless Norway and the kindness of strangers. One of these strangers sparks a separate project Come, for now all is ready, a story about a parish priest off the rugged Helgeland coast, a project now in its third year.

Du Er Her No / You Are Here Now

Du Er Her No / You Are Here Now

The book is almost done. You Are Here Now. Book number two since the break-up with Oslo. My subjective journey through Norway, edited from images dating back to 2008. A book where I come to terms with the elusive notion of home and redefining it in the process. A project said to ‘linger somewhere in-between the genres of documentary and fine art’. What happened in Dhaka four years ago was also about breaking repetition: not to shoot the same images, not to reinforce the stereotypes I see from both Norway and the other countries in which I’ve lived and worked. A feeble attempt to offer new perspectives using the incredible power of photography.

You Are Here Now is just about to hit the press. Now there’s a new visual fatigue: the vacuum created by giving birth to large projects. The past three years have been exceptionally fertile, digging into long term projects, and now there’s both the release of the book and the exhibition of Come, for now all is ready at Perspektivet Museum.

For me, transitions have always been the result of a certain level of discomfort – as have most good stories – whether physical discomfort from a blazing tropical sun or the arctic winds sweeping across the ocean, or the mental challenges sparked by fear, hunger or pressure.

I wish I had that cell and mattress again, that space to think and merely exist. A place to spawn new visual joy and a new direction.

The images from Dhaka have turned into the book Here (Hit), a collaboration with poet Gro Dahle. You can find it in libraries across the country.

The images from Norway are about to be released in book form as You Are Here Now (Du Er Her No) by Tartaruga Press (UK). They have also been exhibited by Trondheim Kunstmuseum, Galleri Lille Kabelvåg and Shilpakala Art Academy.

The images from Come, for now all is ready will be exhibited from November at Perspektivet Museum.